Lean, at its heart, is about finding the root causes of problems that prevent you from achieving your goals.

Lean, at its heart, is about finding the root causes of problems that prevent you from achieving your goals.

Often, what stands in the way of identifying those causes is a lack of discipline. You need a mindset of relentless curiosity and a determination not to settle for easy answers. This brings us to the method known as 5 Whys.

The concept of 5 Whys is exactly what it sounds like: when you’re looking for a root cause, always ask “Why” five times, because until you do, you haven’t explored the idea deeply enough. The idea was developed by Toyota founder Sakichi Toyoda as the basis of the company’s scientific approach to decision-making. Toyota’s leaders have long believed they create a competitive advantage by training all their employees on this method of problem-solving.

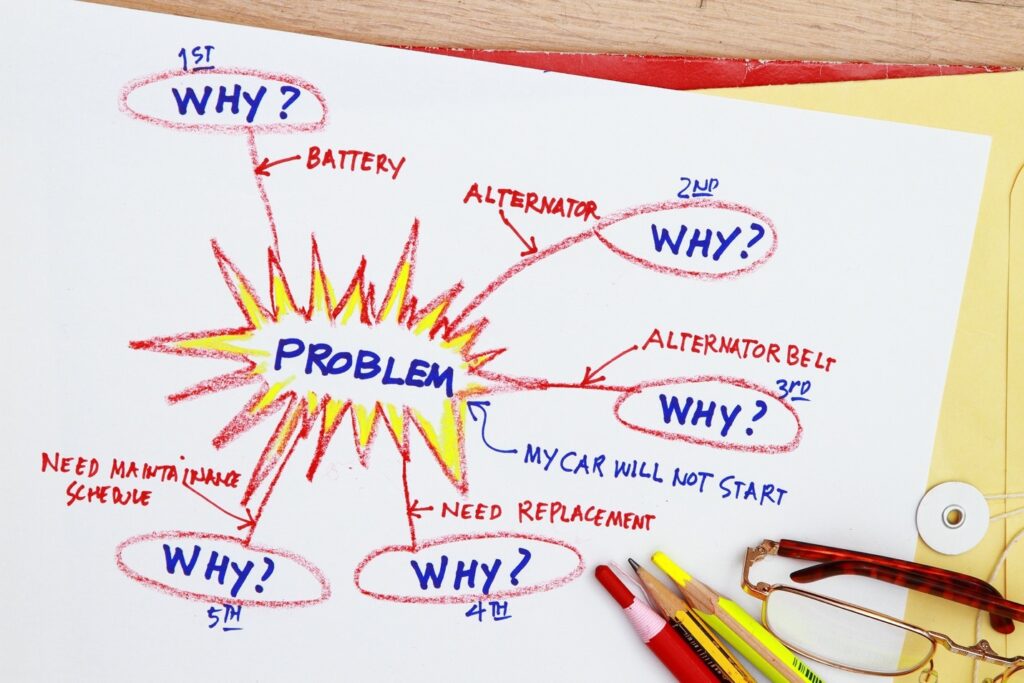

In the common example illustrated below, the problem is that the car won’t start. Why? Because the battery is dead. Why? Because the alternator isn’t working. Why? Because the alternator belt is broken. Why? Because it wasn’t replaced on schedule and was living on borrowed time. The real root cause is only discovered on the 5th “Why.” If you’d assumed that any of the first four answers was the root cause, you’d have chosen the wrong path to a cure.

The 5 Whys sound simple enough to execute, but it’s way too easy to fall into the trap of not having patience or an open mind. Many times, teams are bored with the obvious answer to the first why and want to skip immediately to the second—much like a two-year-old asks “why?” again before you’re even done answering the question. They leap to finish the exercise without ever questioning their own myopic perspective.

But a quick finish is not the goal. The goal is to really know by “going and seeing” where the work is happening. Toyota calls this going to “Gemba” or “Genchi Gengutsu” (the actual part, the actual place).* In manufacturing, that means answers aren’t to be found in the conference room, but on the shop floor.

In business processes, this means you must include the people doing the knowledge work as you’re asking questions. And where the “place” is an office—real or virtual—or the mind’s eye, you’ll need to use a visual management tool to do the seeing, such as SIPOC, high-level process mapping, value stream mapping, spaghetti diagramming, and cause-and-effect (fishbone) diagramming. All these tools are broad in finding potential problems; the 5 Whys is the tool that allows you to go deep. (Just make sure you are focusing on the important few—the constraint.)

Go with a Guide

It’s important that someone act as a neutral facilitator to help your team through this process. One that can diplomatically overcome the workplace dogma that’s ingrained in all of us—the idea that things have always been done a certain way and cannot be changed. It’s the job of a facilitator to question those assumptions tactfully and accept nothing at face value.

When I play this role, I imagine myself as Peter Falk in his Columbo role. Detective Columbo always allows an interviewee to speak and accepts the input so that the interviewee feels heard and validated. Then he says, “Just one more thing”—or, “I forgot to ask.” What I’m looking for is a causal chain leading back to the root cause instead of the symptom. This is systems thinking versus event thinking.

Let me provide an example I cited in a previous post:

I once worked with a client who was a senior buyer for aircraft component repair. Hundreds of parts were backordered, increasing the lead time for repairs and triggering penalty discounts on customer invoices to the tune of hundreds of thousands of dollars. The buyer was purchasing parts reactively at higher costs, and often with expedited shipping. She spent a lot of her day just tracking the status of orders and providing reports. The value stream map showed that what she did was mostly non-value-added—her team thought her job should probably be eliminated, and she was inclined to agree (she hated what she was doing).

But this was her actual job description: to provide parts on time to the first line technician while balancing low inventory. That’s a valuable job, not one that should be eliminated. So the team worked to eliminate her non-value-added tasks so she could spend more time on balance forecasting and reducing inventory.

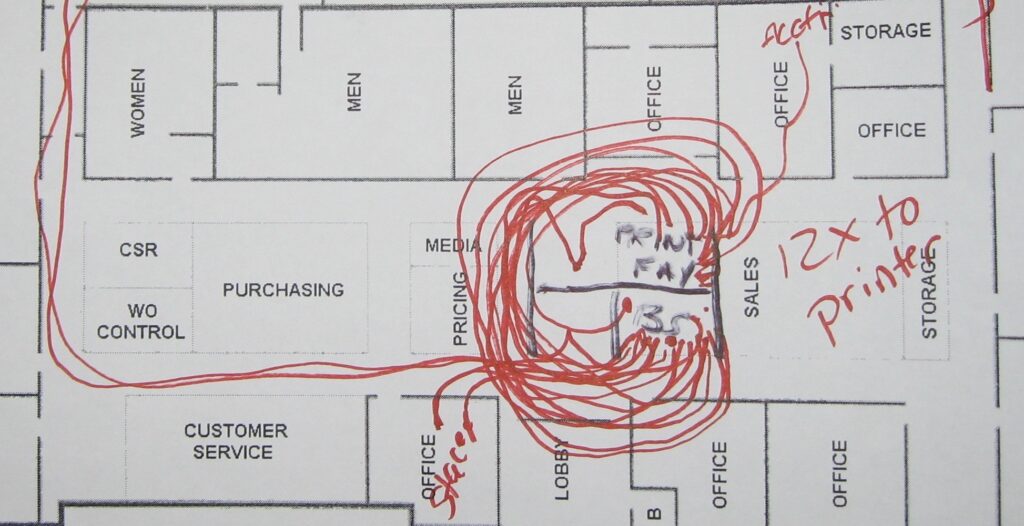

One of the non-value-added activities keeping her from proactively ordering parts was discovered during a spaghetti diagramming activity (a visual representation of motion or transportation waste). The buyer made 12 trips to a printer every day that was located in an adjacent cube with a wall in between.

What solution would you propose to add value—buying her a printer for her desk? It looks like a quick fix that would save a bunch of time, and I was tempted to suggest it. But sometimes quick fixes hide bigger problems. I remembered what my friend and colleague Keith Leitner often told me about good facilitation: “trust the team, trust the tools.” So I continued asking why.

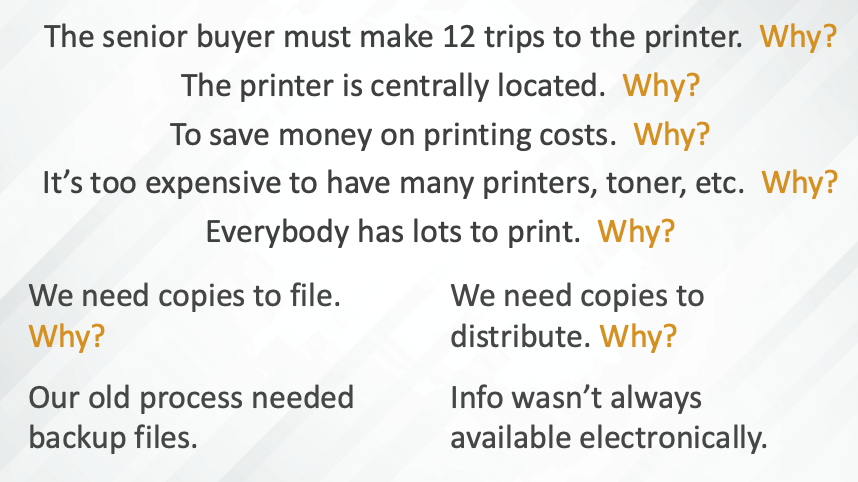

As it turned out, this 5 Whys became 6 Whys and had a fork at the end of the road. The current process was established before most information was electronic. Filing copies was not actually necessary anymore because the server backed up all electronic files nightly. People who received print copies didn’t need them—one person never looked at the copy, one person filed the copy but didn’t know why, and the last person used the copy but would have preferred looking up the info on the intranet in real time.

What would have happened if they bought the buyer a printer? It would have camouflaged the waste. (And before you say this example is outdated, I should tell you that you’d be surprised how many organizations still rely on paper in their processes!)

The team remained persistent in finding real root causes over time. Overall, the company’s efforts to apply lean business processes improved metrics almost everywhere, including reducing inventory by 39 percent and growing its profit margins by five percent. It created excess capacity in facilities and staff that could be used for expansion without additional capital outlay.

Is This Thing Working?

To know if you’re headed in the right direction, here’s a hint: start at the end of your list of answers—at the final root cause you’ve determined—and read your answers from the bottom up, adding the word “therefore” to each phrase. Using the example above, your list would read,

- Our old processes needed backup paper files, therefore,

- we needed paper copies to file, therefore,

- everyone had lots to print, therefore,

- separate printers and toner became way too expensive, therefore,

- we needed to save money on printing costs, therefore,

- we used just one centrally located printer, therefore,

- the buyer had to make 12 daily trips to the printer.

If the sentences make sense this way, going from the bottom up, then you’ve mostly likely discovered the causal chain. If not, you need to take a closer look at your assumptions.

Keep in mind that the 5 Whys represent a new mindset that will take some adjustment, so keep practicing and have patience with yourself. Said Millard Fuller, founder of Habitat for Humanity: “It’s easier to act your way into a new way of thinking than to think your way into a new way of acting.”

Before long, it will be totally natural to follow up the answer to any question with . . . “But why?”

*Liker, Jeffery K. and Meier, David. The Toyota Way Fieldbook. The McGraw-Hill Companies, New York, New York, 1990.

Bill,

Great post; I especially find this useful when dealing with quality escapes. One must always go to the source of the issue or problem at hand in order to effectively have a good starter point. Often times people will tell me they have no issues and al too often they haphazardly discovered they had hidden waste all the time. Asking why helps get to the heart of the matter. Thanks for the post and the reminder to take on a why mindset

Comments are closed.