“Things alter for the worse spontaneously, if they be not altered for the better designedly.”

—Francis Bacon, British philosopher and scientist (1561–1626)

Remember Sisyphus from Greek mythology? This poor guy’s predicament is a profound metaphor for the average workplace.

In the myth, the gods punish the cunning Sisyphus for trying to cheat death—by giving him a much worse fate. His task is to roll a massive boulder up a steep hill, only for it to roll back down every time it reaches the summit. And then he must start again, for all eternity.

Sounds familiar.

Business tasks and processes are often reinvented from scratch every time they’re performed. Despite our best efforts, the boulder just keeps rolling back down to the bottom of the hill, and we start again. We work harder and harder and spend more hours on task—mainly to come up with different ways to do things we were already doing.

What if, instead, you could wedge a chock under the boulder of work to keep it steady, so that you don’t repeatedly start from square one? And what if that chock could be placed progressively higher and higher, so that you could build on what you learn and keep improving? And—gasp—actually reach the top of the mountain?

It’s too late for Sisyphus, but it’s not too late for you. Standard work is the chock that keeps your boulder moving uphill, and it’s the only way to reach your highest goals.

The Enemy: Entropy

Here’s a universal truth in the workplace: as soon as a process is created, it begins to devolve and change. Why?

- Differences in staff experience and background

- Employee turnover

- Inadequate training of new hires

- Cutting corners to expedite

- Departmental mergers and splits

- Shifting customer preferences

- Technology becoming obsolete

Soon, the entropy shows up everywhere—both between and within people, departments, and locations—and multiplies. And that’s despite the fact that our goals generally stay the same, and very little of what we’re doing is novel or original. This leads to the dreaded 8 Wastes: lack of organizational focus, work in process (WIP), transportation, motion, waiting, defects, overprocessing, and overproduction. From there, it’s a short drive to increased costs, employee burnout, and unmet goals.

That sounds like an exaggeration, but it isn’t. Entropy creates huge problems out of small missteps.

There’s an easy way to visualize this that always leaves my class in stitches.

I take my LABP participants out of the classroom and line them up an arm’s length apart, facing right. I tap the first person on the right on the shoulder to turn them around. I then perform an “expert” silent demonstration on how to kick-start a motorcycle and ride it. That person then taps the next person and demonstrates the same action for them, and so on down the line through all the participants.

The action immediately begins to twist away from its original intent in every way physically possible, from missing key parts to embellishing others, and hilarity ensues. I record a video as it happens, and we all go back to the classroom to review, which never fails to entertain every person who contributed to the breakdown of the process. They point out the silly changes they made along the way and laugh some more. Then I ask them, “Is this similar to your organization’s on-the-job training program?”

More than one person will inevitably say, my program isn’t even that good. There wasn’t a proper handoff of duties or a demonstration of expectations. I never laid eyes on the person I replaced, so I created my role from scratch, starting with trial and error and building each process anew.

Variation has a cost even when it doesn’t cause defects. Variation in output, timing, style, and substance makes it harder for the customer (internal or external) to plan, process, and create their own standard work, causing stress. If one person is out of the office, work stops, making the process dependent on heroes who rush in to the rescue.

Standard work is the cure for these ailments.

Defining Standard Work

“Without a standard there is no logical basis for making a decision or taking action.” – Joseph Juran, quality control pioneer

First, let’s talk about what standard work isn’t.

Standard work is not company policies, laws, regulations, or organizational values. Those are developed at a high level and are too broad to govern processes at the point where they’re implemented. Even if the policies are consistently passed on to those new in their roles—and the exercise above demonstrated how easy it is to introduce variance at that step—they can be interpreted in as many different ways as there are workers operating under their umbrella. Processes can be compliant with company policy and still vary wildly in execution.

Standard work is the documentation, communication, and storage of best practices for a particular process by the employees actually performing the work (and developed at the location where the work is done, known in lean as “gemba”). It is the safest, easiest, most consistent, most efficient, highest quality method known to man for performing a task.

Standard work limits non-value-added steps and variation, eliminates errors, and reduces touch time, cycle time, and lead time as you work to achieve your goal. Under the right direction and motivation, employees will create it, hold themselves accountable to it, and even raise the bar by improving it.

The implementation of standard work involves several key steps:

- Observation and recording: breaking down processes into steps and identifying the current method of operation (value stream mapping)

- Defining best practices: collaboratively determining the most effective way to perform each step

- Documentation: creating accessible, visual methods sheets, checklists, or process maps that clearly outline the standard

- Continuous improvement: regularly reviewing and updating standard work to incorporate improvements and best practices, also known as Plan, Do, Check, Act (PDCA)

Here’s an example I lived directly: when I was a general manager over marketing and sales development, the interaction between our sales managers and lawyers on multimillion-dollar proposals and contracts was so slow and iterative that customers would simply leave the negotiating process while waiting for internal approvals.

A superficial look might have suggested that this was the nature of the beast, and that it takes iterations to perfect a contract. But we were losing customers—and even when we managed to close the deal, the outcome was never perfect, and it was generally late. Contracts often consisted of cutting and pasting the parts of previous contracts that made it through approval, leading to a patchwork of language that introduced more errors into the process. Even if we could have hired more lawyers to speed up legal review, what were the chances that would have simplified the process instead of creating more chaos?

Our root cause investigation found that each of the seven sales managers submitting proposals/contracts had their own unique versions that had evolved from varied past experiences, and all continued to be adjusted along the way, creating seven paths going in seven different directions. This meant that every day was a new day for legal to review and approve those documents. Even though none was technically wrong legally, the variation caused excess scrutiny and dialogue to get everyone on the same page. This created slow results, higher work in process, a lot of switching priorities to address the squeaky wheels, and then finally compromising quality and content to meet the deadline—or losing the customer altogether.

After identifying the root cause, the need for standardization was obvious, but still not easy to achieve. Each manager preferred his or her own contract. If we picked one to use as a template, only one manager would be satisfied. So we used a facilitation technique called single text negotiation to get the best contributions from each sales manager and allow them to collaborate on a solution—the best way to get buy-in. The new contract template was better than any of the others standing alone. The result was that these multimillion-dollar proposals and contracts were approved in a few days instead of a few months.

Knowledge Work Is Unique

In manufacturing, standard work is easy to define. You lay out the steps, perform them exactly the same way every time, and refine them as needed. The benefits are also obvious. Generally speaking, you want a car assembled by someone following a standard, not inventing things on the fly, or providing some unexpected artisanal flair.

Knowledge work, the kind that occurs in the business office, involves more complex processes that present more chances for variation to creep in. Knowledge workers aren’t there to assemble cars—they’re there to keep the business running despite a constant stream of distractions.

That’s why when we create standard work for knowledge professionals, it should work more like a cheat sheet than a how-to manual. Standard work offers a way to remind staff of key steps for each process that are often forgotten or missed, rather than train them to follow a process in lockstep. It assumes a skill set and training commensurate with the job requirements.

“People need to be reminded more often than they need to be instructed.”

—Samuel Johnson, English author (1709-1784)

This is where the lean concepts of point of use, visual management, and standard work come together. We want to create an easy-to-access visual cue that helps employees perform work without errors or variation—and it doesn’t have to look the same for every organization. There are many ways to do it, so choose what works best for you. It could be as simple as a checklist, or as detailed as a hyperlinked map that walks through every step of a process.

The only requirement is that the information be simply and clearly conveyed. If it’s too complicated, long, or punitive (say, with signatures required), it’s likely to be disregarded. Again, think “cheat sheet.” It should be designed to be pulled at the point of need—embedded into the process—rather than pushed en masse, as a batch, outside the context of the process, making it likely to be shelved and forgotten.

According to a study published in 2009, surgeons who followed a simple 19-point checklist reduced death rates by more than 40%.

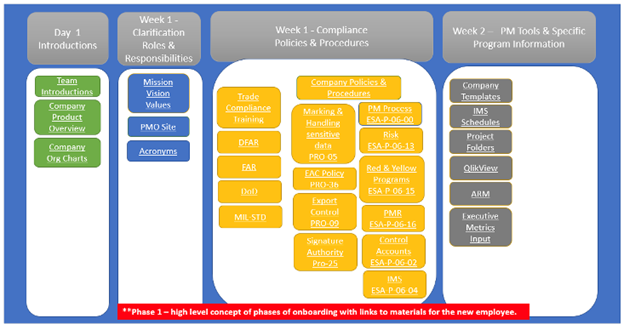

Here’s an example of a highly effective cheat sheet created in PowerPoint embedded with hyperlinks:

The supervisor who created this had noticed that new employees attending orientation and onboarding often became overwhelmed with all the new information provided within the first couple of weeks, especially without context. They frequently had to ask how to find the right information in its many locations. So the supervisor developed this resource, which proved to be so helpful that it was duplicated for all the many different tasks and roles of a program manager.

When we implemented a similar process map for Air Force Acquisition to deal with the arduous process for requesting federal funds, lead times for contract proposals and awards were cut 50 percent.

Benefits of Standard Work

Adopting standard work makes good things happen:

- Reduced variation, reinvention, and rework

- Less lead time and lower costs

- A clear standard against which employees can measure their work

- Transparency that limits the potential for abuse or fraud

- Improved clarity and efficiency in turnovers

- Enhanced ability for employees and substitutes to contribute effectively

- Less organizational stress

- Sustainable use of natural resources (less paper, less cloud storage, etc.)

- A collaborative environment that fosters synergy and innovation

One of the great unsung consequences of implementing standard work is that it provides employees with a sense of professionalism and pride. They themselves have defined the standard, so living up to it becomes a point of accomplishment and improves their self-esteem.

Get Your Customers on Board

Although most variation is related to internal processes, customers (internal and external) also get in on the act. They treat us like we’re Burger King, expecting to “have it their way.” But even Burger King has a menu. In business processes and especially knowledge work, we invite unneeded variation by not providing customers with a menu of choices.

Sometimes the customer needs a specialized knowledge product from your department, but they don’t know what that product is. You’re the expert, so help them out by telling them up front what you think they need and offering solutions in menu form, allowing them to choose predictable outputs. That way, you can have templates and checklists already developed—and a good idea of lead time and costs. Even if the customer requests a tailored solution, you’ll benefit by starting from a standard. You’ll spend less effort on standard menu items, freeing up more time for one-off or more in-depth requests.

Why Do We Resist Standard Work?

It generally comes down to power and ego.

The most stubborn obstacle to implementing standard work is the phrase “but that’s the way we’ve always done it.” Yet the odds say that phrase isn’t even true—a process that isn’t standardized evolves (or devolves) every time it’s performed. But the idea of change causes anxiety, and so workers and leaders exert control by becoming heroes: the keepers of a process that only they can carry out. Heroes hoard information, have their own workarounds, and make processes much more complex than they need to be. They hold the organization hostage instead of being transparent and open.

Managers who resist standards can be as capricious as they like when they review or approve, and keeping the status quo guarantees them more power. They optimize the system for themselves rather than for the goal. They reject the chance to make processes flow (by establishing an objective standard for the review process) for the illusion of control.

Another reason companies may reject standards is a false idea of what the word “standard” really means. For some, it may connote mediocrity, or boredom. I often encounter the idea that implementing a standard will stifle creativity. But what “standard” means in the context of business processes is a model of excellence, not a lack of innovation. (Etymologically speaking, it also includes the idea of a banner in battle or a rallying place. Spot on!)

Who wants to waste their creativity reinventing a business process when they could be improving that process instead—and moving on to other more interesting challenges that require novel thinking? Just as artists set up their tools consistently before they work, standardized processes provide a stable foundation for innovation by eliminating waste (set-up time) and variability.

Standard work is not merely a set of instructions; it’s a philosophy that underpins a culture of excellence and continuous improvement. By embracing standard work, businesses can not only achieve operational efficiency and consistency but also create an environment where creativity and innovation flourish. It’s about setting the bar high and striving for excellence in every aspect of business operations. As Vince Lombardi famously said, “Perfection is not attainable, but if we chase perfection, we can catch excellence.” Standard work is the pathway to catching that excellence—or at least a wedge to prevent us from rolling backwards.