In the business office, we often tend to think of the deliverables we produce in terms of a rate. For example, we might have 10 reports, or 100 invoices, or one closing of the books, to complete in a month.

And so we view the end of the month as our deadline, with x units to be delivered by the end. Sounds like a reasonable enough plan—why doesn’t it work? Why are business processes always falling behind?

Because we’re defining deliverables in terms of ourselves and our own schedules, and not in terms of what the customer needs (whether that customer is internal or external). Welcome to the concept of takt time.

Calculating Customer Demand

Takt is the German word for “beat,” as in music. It’s the rhythm you must maintain based on customer demand. And once you understand the concept, you’ll realize processes shouldn’t be created to serve any other master.

Takt time is calculated with a simple formula, but it’s still one of the most difficult concepts for people to understand when they first learn lean, because it’s different from the way we normally think. Applying this concept in the business office isn’t simply adding a twist to traditional manufacturing practices—it really requires an open mind to conceive and internalize.

The formula? The time you have available to do the work, divided by customer demand.

The answer is a unit of time. If the customer demands eight units in an eight-hour day, then the takt time is one hour. That means the customer demand is one unit every hour. Traditional management tells us we have to complete eight per day, which is a rate; one every hour is a takt time. It’s the difference between measuring how many gallons per minute flow out of a water hose and measuring how many minutes it takes to get a gallon.

Why does it matter? Because using a rate doesn’t communicate a sense of urgency. It tempts you to procrastinate and overestimate how much you can get done by a deadline. And a rate doesn’t give you a way to measure whether your process is capable—whether it can be used successfully to satisfy customer demand. Takt time does both.

Takt time . . .

- sets a cadence or rhythm so you can sync with others and avoid waste

- limits batching, creates a sense of urgency, and increases situational awareness

- requires that you reduce variation by creating standard work

- defines the limits of different steps of your process to make it capable

- exposes time constraints—any step that is greater than takt time must be shortened or offloaded

Takt time in manufacturing offers an easy-to-understand illustration of what I mean. Take Toyota’s process for the Camry. From Factory Physics for Managers*:

For example, suppose the demand for the Camry is 600,000 units per 250-day year. This translates to 2,400 units per day or 1,200 units per 12-hour shift. For a manager scheduling the line to work 10 hours each shift, the takt time will be 30 seconds (10 hours x 60 minutes x 60 seconds/1,200 = 30 seconds).

In other words, a Camry has to move off the production line every 30 seconds. Talk about your tangible sense of urgency!

Translating Takt Time to the Business Office

How does this concept work outside manufacturing? Let’s take accounts payable as an example. Assume you need to process 100 invoices per month on average, and you have 160 available hours in which to do it.

160 hours/100 invoices = 1.6 hours takt time

One unit needs to be completed every 1.6 hours. In creating your standard work, you need a process that takes less than 1.6 hours (that’s known as your cycle time); otherwise your process is not capable. To meet demand with a longer cycle time, you may need more people, or you may need to carry more work in process (WIP), but both are additional costs. Without the situational awareness of takt time versus cycle time, how would you know how to address issues that arise?

If you go with a rate instead, making your goal 100 per month, you’ll tend to batch work and experience “student syndrome,” or waiting until the last possible minute to achieve the entire goal, which almost guarantees failure to satisfy the end customer.

I work with an international corporation that hires 25 new people per day. If you look at just the work required to enter new hires into the system, the takt time is 480 minutes per day divided by the 25 new hires, which equals 19.2 minutes apiece. One must be entered into the system every 19.2 minutes; luckily, the touch time (cycle time) for each is only 12 minutes. That’s a sign the process is capable, and that adequate cushion is built in.

If you can’t meet takt time because customer demand is greater than your cycle time and there’s no way to make your process 100% capable, you should still operate using a planned takt time so that different parts of the process are synchronized, and accept that you can’t serve every customer the same way.

Instead, you can set your takt time to the pace of your constraint. The finest restaurants can’t meet their customer demand for reservations on a Friday night. But they don’t just stuff folks in and turn their tables every 30 minutes in hopes of trying to serve everyone. They establish a takt time and induct new customers at that speed. The wait staff and the kitchen are set up accordingly.

Takt Time for Multiple Steps

For more complex processes, computing takt time is an absolute must to avoid blaming the wrong cause when something goes awry.

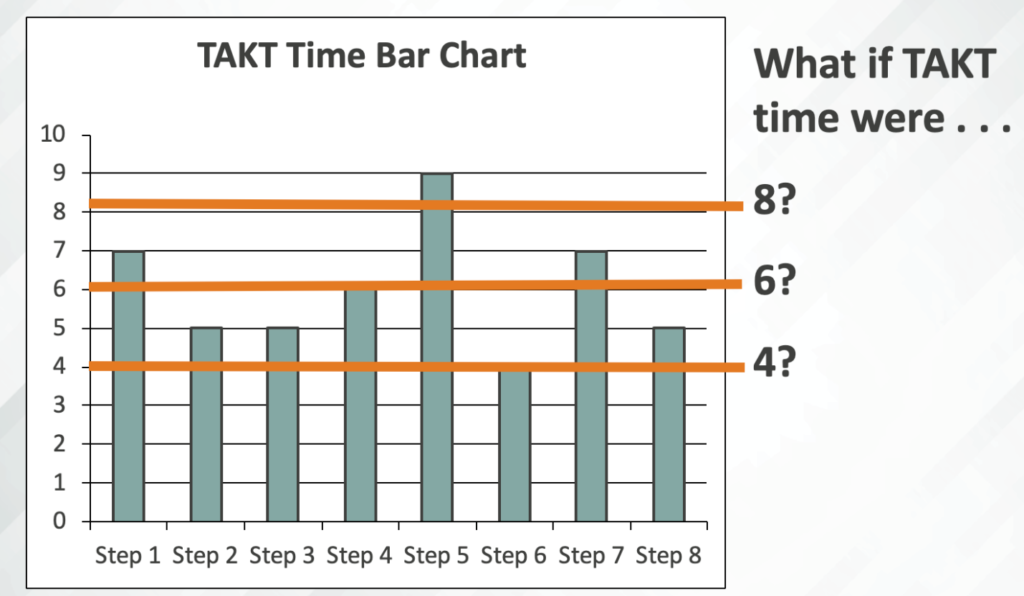

The illustration below represents a process that takes eight steps to produce one output. Each step varies between four and nine hours (cycle times). But the customer demands that one should be completed every eight hours—that’s the takt time. For a continuously repeated process, you can see that Step 5 is a constraint (a kink in the hose), because it takes nine hours to complete and therefore delays Step 6. The customer can’t get a product every eight hours, so there’s no way to meet takt time, and the employees responsible for Step 5 are set up to fail. They’ll end up scrambling and likely compromising quality and content to meet deadlines.

What if the takt time were six hours? That would mean that Steps 1, 5, and 7 were not capable. Also, in Steps 2, 3, and 8, cycle time would be equal to takt time. When takt time and cycle time are equal, there’s no room for any variation—even a sneeze can get you behind and create a panic.

Toyota, the pioneer of lean manufacturing, has the least variation of any organization, but it always builds in ample cushion; when something should take 10 hours, managers schedule 12, or a 17 percent cushion.* Any leftover time is used to improve the process. Goodyear Tire, as another example, uses a 30 percent cushion. Your business processes probably have a lot more variation than either of these manufacturers. How much cushion should you build in?

Also, you must be literal about available time. If your work day is eight hours and you allow two breaks of 15 minutes (morning and afternoon), then the available time is not eight hours, but only 7.5 hours, or 460 minutes. So, if customer demand is eight units per day, the takt time is now 460/8, or 56.25 minutes. If you set up a process that takes an hour, but the demand is really one unit every 56.25 minutes, you’re setting your employees up to fail.

Same goes for a yearly process where you use 365 days as available time, without subtracting holidays or weekends, requiring heroes to step up and work themselves to death to meet demand. It’s simple math that shouldn’t be hard to grasp, yet it happens over and over again in organizations for no good reason.

Takt time can apply to any process in the business office: purchases, project management, engineering documents, sales proposals, and on and on. And once you’ve got the hang of computing it, you can take a look at all your processes and see whether your assumptions about customer demand can be challenged for better results. For example:

- Personnel evaluations. Is yearly really the right drumbeat? Why not do them monthly so you can thank a good performer at least 12 times and address poor performance sooner?

- Strategy deep dives. If your situation changes more than once in a year, quarterly is better than yearly.

- Budget projections. An 18-month forecast delivered monthly can take less time and make you more agile than a yearly projection that can’t adjust for changes.

You could create standard repeatable work for each of these that actually takes less time than a yearly approach. And your customer—whether internal or external—is much more likely to be satisfied.

Using lean to improve your processes requires that you begin to understand and visualize customer demand. Takt time is a crucial piece of that puzzle. Once you start using it, you’ll wonder how you ever set up processes without it. But without it, in all likelihood you’ll be marching to the beat of the wrong drum.

Take a minute now and think: what’s your takt time?

*Citation: Pound, Edward S., et. al. Factory Physics for Managers: How Leaders Improve Performance in a Post-Lean Six Sigma World. McGraw-Hill Education, 1st ed., 2014.

Very good blog

Comments are closed.